Technical software documentation is not merely a formality but a way to understand the entire software development lifecycle. It offers huge benefits for developers, users, and the company alike.

Technical documentation is the foundation of every sustainable software project. If software development is like building a complex machine, technical documentation is the owner’s manual, the full blueprint, the team’s shared notebook, and the training simulator.

Without proper technical documentation, the software might run. Still, only the original builders know how to fix it, sell it, or teach others to use it, assuming they have a big memory. The lack of documentation limits long-term potential and makes every maintenance a slow, costly guess.

This guide breaks down the types of technical documentation, shows how they connect to each stage of the Software Development Life Cycle, and shares best practices used by leading engineering teams.

What is Technical Documentation?

Technical documentation in software development is a collection of guides and articles that help developers and users understand software. It explains how software works, how to use it, and what features it offers.

Documentation assists developers in building and maintaining software properly, helps users use it and troubleshoot themselves, and guides stakeholders in making effective decisions.

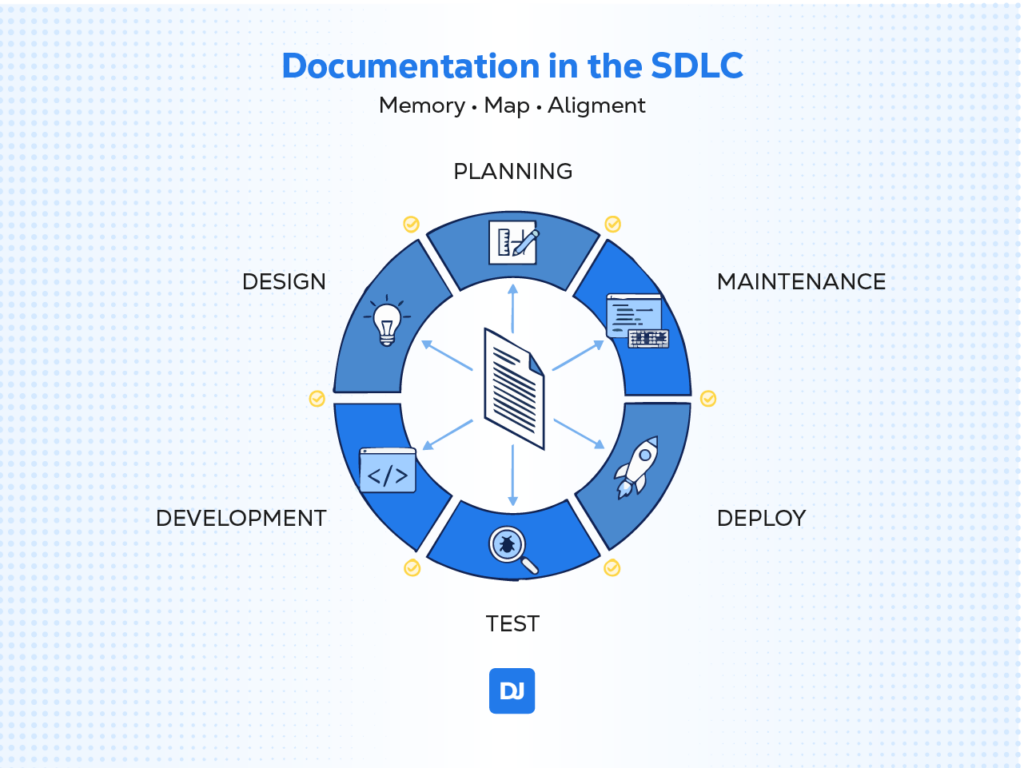

Why Technical Documentation Matters in the SDLC

Technical documentation acts as the company’s memory and the system’s detailed map. Here are the main benefits and importance of technical documentation in the Software Development Life Cycle (SDLC), focusing on the development team and long-term project health.

1. Maintainability and Sustainability

Technical documentation leads to rapid problem identification. Developers can locate the source of a bug or performance bottleneck faster using architecture diagrams, data flows, and implementation details (APIs).

Documentation also records past design decisions (why technology X was chosen instead of Y), preventing the team from wasting time rehashing issues already resolved or, worse, breaking the system by introducing conflicting changes.

Finally, as the system ages, documentation becomes essential for understanding legacy code that has not been touched for years, transforming “black box code” into a manageable asset.

✅ Result: Less technical debt, faster fixes, and a system that grows without chaos.

2. Ease-to-use and Onboarding

Technical documentation provides a structured guide from scratch. It doesn’t depend on “pulling” knowledge from senior developers, who may be busy with improving the onboarding of new team members. Moreover, knowledge of the system’s inner workings doesn’t get stuck in the heads of one or two individuals (the so-called Bus Factor). The documentation ensures project continuity, even with high staff turnover.

✅ Result: Smoother handovers, shorter onboarding time, and higher team autonomy.

3. Collaboration & Alignment

In large projects with multiple teams, technical documentation aligns everyone to use the same components and services, promoting cohesion and integration. Plus, a developer can read the code documentation (Javadoc comments, docstrings, etc.) without asking for help. Technical documentation makes development more productive and autonomous.

✅ Result: Consistency across projects and predictable delivery.

4. Quality and Design Improvement

Confusing code is revealed when attempting to document it. Documenting decisions reveals clearly more about the code structure and logic. In open-source software projects or those focused on public APIs, technical documentation is part of the product. High-quality documentation translates into a high-quality product.

✅ Result: Cleaner architecture and fewer bugs downstream.

5. Infrastructure and DevOps Stability

Technical documentation also describes environment configurations (for deployment and Infrastructure as Code). Documentation ensures software functions correctly across all environments (Development, Testing, Production). In production downtime, documentation on the architecture and critical logs supports troubleshooting, diagnosis, and rapid problem-solving.

✅ Result: Fewer release failures, stable pipelines, and easier troubleshooting.

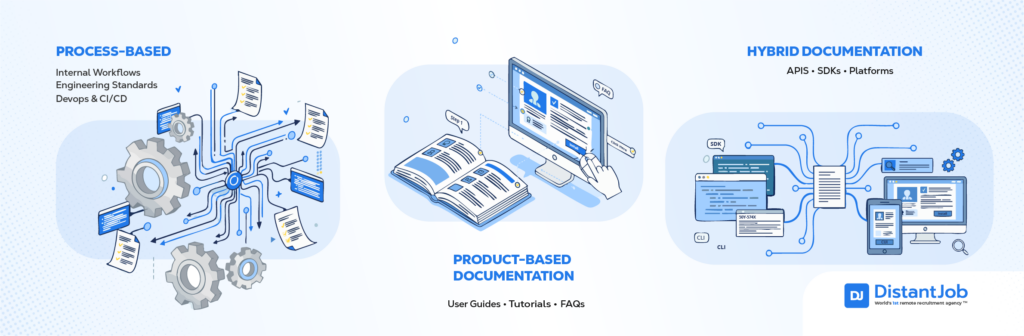

3 Types of Technical Documentation

Technical documentation can be classified in various ways, but a practical method is to categorize it based on its primary audience and purpose.

For software development, we can group it into three main types: Process-based, Product-based, and a “Hybrid” category for technical products.

1. Process-based (Development and Internal Stakeholders)

Process-based documentation describes how development work is done internally. It’s not what the software does, nor how third parties should use it. Instead, it records methods, workflows, standards, technical decisions, and operational practices that guide the engineering team day to day.

The goal is to ensure consistency, reproducibility, and continuity in development, even when there is a change in personnel or teams.

It serves as a technical institutional memory: a living manual that guides decisions, practices, and responsibilities.

In mature teams, process-based documentation follows the “process as code” principle. Processes are formalized, versioned, and revisable, often stored alongside the code (e.g., Git repositories, Markdown, ADRs).

We can divide process-based documentation into a few common categories:

| Category | Description | Typical Example |

| Development Processes (SDLC) | Defines the software lifecycle, development, review, and deployment steps. | “Our PR and code review process follows three steps: automatic review, peer review, and merge into main.” |

| Engineering Practices / DevOps | Records how the team handles builds, testing, deployments, monitoring, etc. | “Every deployment goes through the Jenkins pipeline with linting, unit, and integration tests.” |

| Architecture and Design Decisions (ADRs) | Explains technical decisions and their historical reasons. | “ADR-004: Choice of PostgreSQL instead of MySQL due to better JSONB support.” |

| Standards and Conventions Guide | Defines coding, versioning, naming, branching standards, etc. | “Branches must follow the pattern: feature/issue-id-description.” |

| Integration and Delivery Flows (CI/CD) | Documents how pipelines are configured and maintained. | “The CI jobs run regression tests in Docker containers.” |

| Technical Onboarding Guide | Helps new developers understand the internal environment and tools. | “To run the project locally, clone the repo and execute make dev-up.” |

| Incident Management and Post-Mortems | Standardizes how the team responds to and learns from failures. | “After every P1 incident, a post-mortem must be published on Confluence.” |

2. Product-based (End-Users and External Stakeholders)

Product-oriented documentation explains how the end user interacts with the software—how to use, configure, troubleshoot, and get the most out of its features. Such documentation translates technical complexity into understandable actions focused on usability, results, and value.

In other words, while process documentation shows “how we build the software,” product documentation shows “how you use the software.”

The end users for this type of technical documentation can vary greatly depending on the type of software:

- Business-to-business (B2B) users: managers, analysts, corporate clients;

- Technical non-developer users: system administrators, data analysts, QA engineers;

- Business-to-consumer (B2C) users: ordinary people who use an application, website, or SaaS tool.

The language level and style of the documentation need to reflect the technical level of the audience. In short, it’s an extension of UX (User Experience) — the documentation should be as clear and accessible as the product’s interface itself.

This type of documentation usually includes several complementary formats, forming an ecosystem of user assistance.

| Type | Description | Typical Example |

| User Guide | Explains the main features and flows of the system. | “How to create an account and configure your profile.” |

| Tutorials / How-To Guides | Show step-by-step how to perform specific tasks. | “How to export reports as CSV.” |

| Reference Manual / Help Center | Gathers detailed descriptions of all functions and menus. | “Description of each field on the Settings screen.” |

| FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions) | Quick solutions for common questions. | “How do I reset my password?” |

| Installation / Setup Guides | Teaches how to install, configure, and start the software. | “Installing the desktop client on Windows and macOS.” |

| Release Notes | Inform about changes, new features, and fixes. | “Version 3.4: You can now import data from Excel spreadsheets.” |

| Troubleshooting Manuals | List common errors and how to resolve them. | “Error 403: Verify that you have permission to access the module.” |

| Best Practices Guides | Show ideal uses or recommendations to avoid errors. | “Use tags to organize your projects.” |

3. “Hybrid” Documentation

The term “hybrid documentation” is not a standard term in the software industry (as are, for example, “User Manual” or “Design Document”). However, this is the context that describes the merging of internal technical documentation and external user documentation.

When the product is technical in nature (such as an API or SDK) the user is also the developer. In this case, the “product” documentation and the “technical integration” documentation end up merging.

Therefore, this type of documentation needs to serve two purposes simultaneously. Teaching what the product does and why it’s useful (product/user perspective) and showing how to use it technically (developer perspective).

Even though it’s technical, the document’s tone changes. The result is a documentation that aims for clarity and didactics. It will show not only code and functionality but videos, tutorials, and user guides.

This mix is inevitable and even desirable, because the success of products for developers depends as much on the usability of the product as on the technical clarity of the implementation.

| Type | Description | Target Audience | Typical Example |

| API Documentation (REST, GraphQL, gRPC, etc.) | A mix between a product usage guide and a technical reference. Explains business concepts and endpoints. | External Developers or Partners | “How to authenticate and submit transactions via the API.” |

| SDK or Library Documentation | Teaches how to integrate the SDK, but also shows use cases and best practices. | Developers using specific language SDKs | “How to integrate the Python SDK to process payments.” |

| CLI (Command Line Interface) Documentation | Explains commands, flags, and the logical flow behind using the tool. | DevOps, System Administrators, and Engineers | “How to use the CLI to provision cloud resources.” |

| Platform Documentation (PaaS, SaaS Dev-Oriented) | Combines a product overview with technical guides for integration, deployment, and automation. | Engineers and Developers using platforms as a product | “How to set up pipelines in GitLab CI/CD.” |

| Infrastructure as Code (IaC) Documentation | Explains both the product (Terraform, Ansible, etc.) and internal usage processes and best practices. | DevOps, Cloud, and SRE Engineers | “How to create and version custom Terraform modules.” |

| Extensibility / Plugins / Webhooks Documentation | Teaches how to extend the product via APIs, events, or scripts. | Developers who build on top of the product | “How to create a plugin for Jira.” |

| Shared Architecture Documentation (for partners) | Explains integrations, dependencies, and flows between external systems. | Technical Partners or Integration Teams | “How the billing system communicates with the ERP via webhooks.” |

| DevTools Product Documentation (IDE, CI/CD, AI coding assistants, etc.) | Blends tutorial (product usage) with technical reference (commands, APIs, extensions). | Software Developers and Engineers | “How to configure Copilot in VS Code.” |

| Internal APIs Documentation (Private APIs) | Serves internal teams, but with a public documentation structure (with guides and references). | Internal Engineering Teams | “How to consume the company’s internal authentication API.” |

| Data and Analytics Documentation (DataOps) | Combines product usage (dashboards, pipelines) with technical details (schemas, ETL). | Data Engineers and Technical Analysts | “How to create new pipelines in Prefect or Airflow.” |

7 Best Practices for Writing Technical Documentation

Technical documentation’s value is in its clarity, accuracy, and usability. Applying the following best practices will ensure your documentation actively supports your project’s success and is truly helpful to its target audience.

1. Know Your Reader

Answer two questions: “What kind of message do you want to convey?” and “For whom?”. Your audience’s perspective is the basis of writing. If possible, take this advice not only for technical documentation, but for life.

Is your reader a developer? If so, is your developer on your team, or are they the end users? What does your reader need to know?

If your reader struggles with overly technical language, consider writing more simply.

It’s not about the type of technical documentation (which is secondary); write for the reader. Choose for clarity over bureaucracy. Your objectives towards the reader come first.

2. Prioritize Real Use Cases

Instead of simply listing abstract functions, focus your documentation on solving real-world user problems. Technical documentation should function like a recipe book, not just a list of ingredients.

Developers and end-users alike are typically driven by a specific task or goal (e.g., “How do I connect to the API to retrieve a list of users?” or “How do I configure the serverless function to run nightly?”). The documentation must guide them through the successful completion of these tasks.

Organize guides around actions and outcomes, not just feature names. Use titles that begin with action verbs: “Setting up X,” “Integrating Y,” “Troubleshooting Z.”

For developer-facing content (like APIs and SDKs), always provide ready-to-use, tested code examples that demonstrate common use cases. A developer should be able to copy, paste, and run the example successfully with minimal changes.

Base your tutorials on common user stories or pain points collected from support tickets, user feedback, or stakeholder interviews. This ensures the documentation addresses the information gaps your audience actually faces.

Supplement complex configuration steps or data flows with screenshots, flowcharts, or diagrams to illustrate the process visually.

3. Stay Consistent

Use the same format, the same body text. Use standardized headings and a Style Guide. Readers prefer a familiar and predictable format. Reading documentation should not feel like reading a book where the style changes every page.

4. Create an Organized Structure

Organize, structure, and label document content to make it findable and understandable for readers. Create a logical and intuitive way for people to navigate information across your document.

For example, in technical documentation, it makes sense to organize by tasks (e.g., “Installation,” “Configuration,” “Troubleshooting”) or subjects (e.g., “Software Modules,” “APIs”).

For step-by-step guides, tutorials, or version histories (release notes), organize topics by time sequence. Plus, create glossaries, indexes, or lists of technical terms.

Documentation must balance precise technical terms (the business/product objective) with terms users usually search for. Precise labeling increases the probability of findability.

For instance, fridge and refrigerator might be different, but they are the same thing in many contexts. It won’t hurt to use them both on an e-commerce website to make the product findable. The same goes for technical terms.

Finally, create a Content Inventory to catalog all existing material (topics, labels, titles). This is great for analyzing legacy content and making decisions on what should be maintained or changed.

5. Collaborate and Review (“Docs As Code”)

Don’t write it alone. Documentation should be a collective effort, subject to scrutiny and feedback from various stakeholders, much like the code itself.

A writer’s perspective is inherently limited by their familiarity with the document they created. The same relationship happens with developers and code, or sellers and their products. Your reader is not you; your user is not you. Knowing their perspective isn’t enough; you need their feedback.

For example, Information that seems “self-explanatory and obvious” to the author may not be clear to the document’s readers. Collaboration and review are necessary to test if the documentation is easy for others to understand. If something is incomprehensible to one person, it is likely incomprehensible to others.

By embracing collaboration and review practices, documentation benefits from the expertise of multiple stakeholders, resulting in content that is accurate, comprehensive, and reader-centered. The technical verification ensures the documentation is accurate and up-to-date.

Just like the code itself, the documentation needs to be reviewed. This is called “Docs As Code”. The review process should involve colleagues and subject matter experts (SMEs) to check for accuracy, flow, and usability. Peer review also tests the technical documentation for usability. Reviewers should check the documentation for factual errors and verify that it is consistent with the current version of the software.

6. “Why” Before “How”

People should know why an action is performed, so they can learn how to do it with proper intent. Knowing before performing satisfies basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness.

Author Simon Sinek’s “Start with Why” concept argues that the most successful leaders and companies inspire action by first communicating their purpose, cause, or belief, before explaining their products or processes. The same thing goes for documentation.

Who Owns Documentation in Modern Teams

In modern, high-performing teams, documentation ownership is cross-functional and shared. The most effective approach is “Docs-as-Code”, which treats documentation as a product asset, integrating it directly into the development and operations workflows.

No single person owns all the documentation; the entire product team shares accountability for its existence and quality. By treating docs like code (using version control, peer review, and automated builds), teams formalize the shared ownership model.

Developers own the accuracy (the “what”), and Technical Writers own the usability and clarity (the “how” and “for whom”). Finally, DevOps controls documentation’s versioning, making it up-to-date and relevant.

Developers (Accuracy and Technical Detail)

Developers are the Subject Matter Experts (SMEs) and have the primary ownership of the technical accuracy of the documentation, especially for code-related content.

They are best positioned to create the initial drafts and in-line documentation while the code is fresh in their minds. Developers also review documentation changes for correctness and completeness, ensuring they accurately reflect the latest code and system behavior.

Technical Writers (Clarity, Structure, and Usability)

Technical Writers own the User Experience (UX) of the documentation and its editorial quality. They act as the “librarians” and “translators” of complex information, and as architects of information.

Writers define overall documentation structure, information hierarchy, and content types (tutorials, guides, reference, explanation). They are also responsible for editing developer drafts for clarity, consistency, grammar, and tone. Moreover, they ensure the content is tailored to the target audience (whether internal or external) and easy to read.

Technical writers often own the documentation toolchain, including the static site generators, version control integration, and publishing pipeline. They make sure the documentation is easily accessible and correctly published.

DevOps (Delivery and Maintainability)

DevOps and Operations teams own the reliability, accessibility, and automation of the documentation infrastructure, ensuring it is a living, maintainable artifact.

Through Docs-as-Code implementation, they facilitate the integration of documentation into the same Continuous Integration/Continuous Delivery (CI/CD) pipelines used for code, ensuring documentation is built and deployed alongside the product.

DevOps Engineers also manage the infrastructure (e.g., Git repositories, build servers, hosting environment) and tooling (e.g., Markdown/reStructuredText processors, documentation generators) that enable the entire team to contribute.

Finally, they ensure proper versioning and synchronization of documentation with product releases and manage the archival of old, outdated versions.

Technical Documentation Templates You Can Reuse

Here are the four templates, clean, structured, and ready for copy-paste into any documentation system.

🏗️ Software Architecture Document Template

Purpose: Explain system design and the reasoning behind architectural decisions.

1. Overview

- System Summary:

- Business Context / Goals:

- Scope & Constraints:

- Tech Stack Overview:

2. Components

For each component, include:

- Name:

- Purpose:

- Responsibilities:

- Dependencies:

- Key Design Decisions:

3. Interfaces

Document how components interact.

- Interface Name:

- Type (REST, Message Queue, Internal API, etc.):

- Inputs / Outputs:

- Protocols & Formats:

- Error Handling:

4. Data Flows

- High-Level Data Flow Diagram:

- Data Inputs & Outputs:

- Data Storage Locations:

- Transformation Steps:

- Performance Considerations:

🔗 API Reference Template (REST or GraphQL)

Purpose: Describe APIs in a structured format for developers.

1. Auth Setup

- Authentication Method: (JWT, OAuth2, API Key…)

- Token Retrieval:

- Scopes / Roles:

- Headers Required:

2. Endpoints

For each endpoint:

Endpoint Name

- Method / Route:

- Description:

- Permissions:

- Examples:

- Successful response

- Error responses

- Successful response

- Status Codes:

3. Parameters

- Path Params:

- Query Params:

- Headers:

- Body Parameters:

- Validation Rules:

4. Code Examples

Include examples in multiple languages where relevant:

- cURL:

- JavaScript:

- Python:

- Node.js Fetch / Axios:

🚀 Developer Onboarding Guide

Purpose: Guide new engineers to productivity as fast as possible.

1. Environment Setup

- Prerequisites:

- OS Requirements:

- Install Dependencies:

- Clone the Repository:

- Environment Variables / Secrets Setup:

- Build & Run Project:

2. Tools

- IDE Recommendations & Plugins:

- Git Workflow:

- CI/CD Overview:

- Documentation Links:

- Project Board / Tickets:

3. First Pull Request

- Pick an Intro Task:

- Branch Naming Convention:

- Commit Message Style:

- Open the PR:

- Checklist Before Request Review:

- Merging & Deployment:

🚨 Incident Post-Mortem Template

Purpose: Analyze incidents to prevent recurrence and improve systems.

1. Summary

- Incident Title:

- Date & Duration:

- Impact:

- Severity Level:

- Systems Affected:

2. Timeline

- Timestamps of Key Events:

- Detection:

- Escalation:

- Mitigation:

- Resolution:

3. Root Cause

- Primary Cause:

- Contributing Factors:

- Detection Gaps:

- Why it Went Uncaught:

4. Preventive Actions

- Short-Term Fixes:

- Long-Term Improvements:

- Monitoring / Alerting Changes:

- Process or Team Adjustments:

| Template | Purpose | Key Sections |

| Software Architecture Document | Explain system design and decisions | Overview, Components, Interfaces, Data Flows |

| API Reference Template | Document REST/GraphQL APIs | Auth Setup, Endpoints, Parameters, Code Examples |

| Developer Onboarding Guide | Help new engineers start fast | Environment Setup, Tools, First Pull Request |

| Incident Post-Mortem | Record and learn from incidents | Summary, Timeline, Root Cause, Preventive Actions |

Conclusion

Technical documentation is a strategic investment that determines a software project’s longevity, maintainability, and capacity for growth. When documentation evolves alongside your code, you don’t just build software, you build organizational memory. Well-documented code isn’t just easy to maintain; it’s easy to trust.

If you are looking for trusted technical professionals, please don’t hesitate to reach out. We have been in the recruiting developer business for over two decades, and we can assist you in finding the right software developer for your team. Book a call today!